The prohibition of nuclear weapons in Latin America

Summary of the main working phases

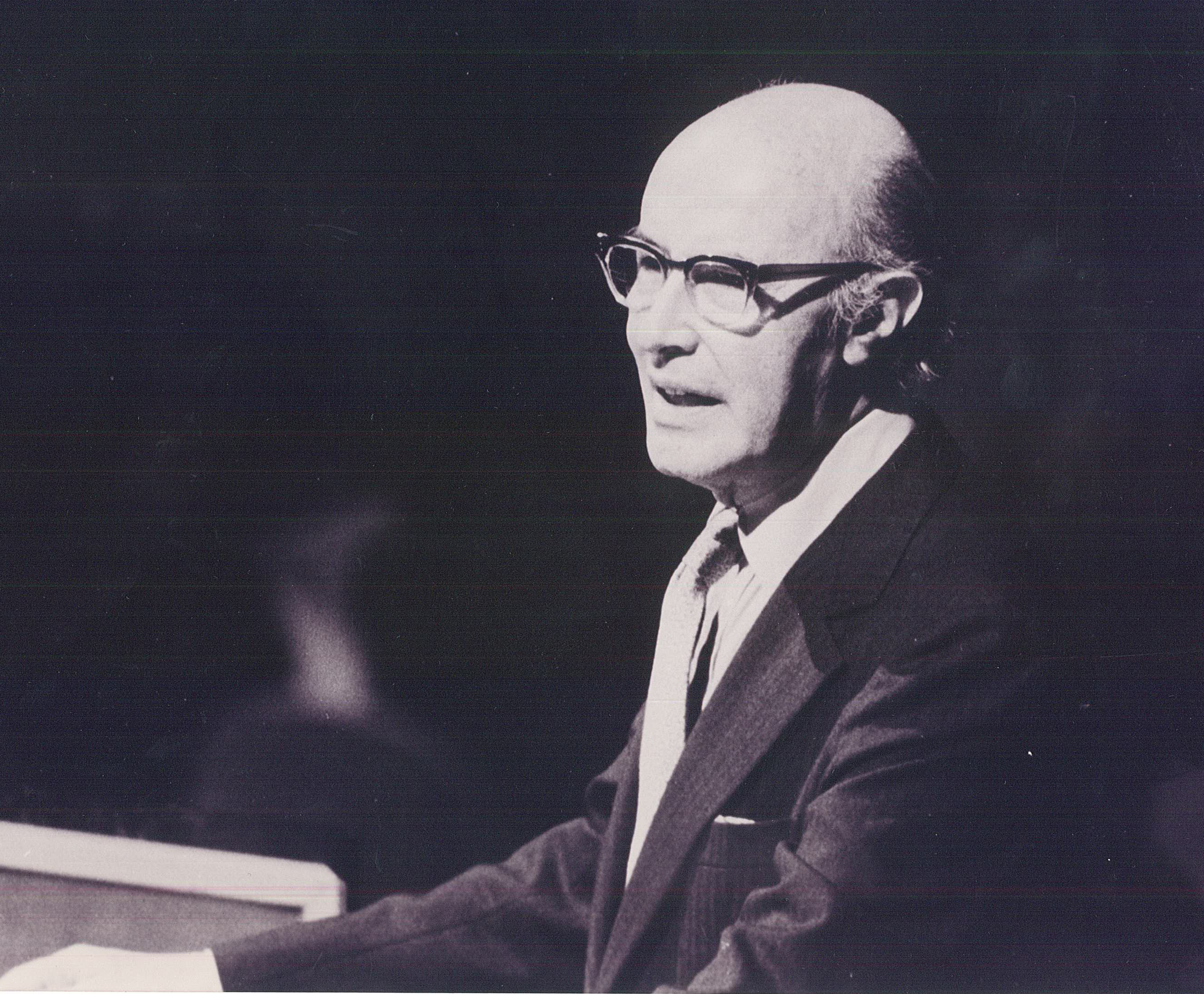

By Ambassador Emeritus Alfonso García Robles*

The enterprise that, by the initiative of Mexico, all the Latin American Republics started in 1963 and finished in February 1967 with the opening for signature of the Treaty of Tlatelolco, has been of short duration if compared with other projects of reaching agreements in disarmament, especially nuclear disarmament.

1.- The Declaration of the five presidents

The starting point of the steadfast efforts that made possible the denuclearization of Latin America was the Joint Declaration issued on 29 April 1963 by five Latin American presidents, led by the then President of Mexico Adolfo López Mateos, who invited the Presidents of Bolivia (Víctor Paz Estenssoro), Brazil (Joao Goulart), Chile (Jore Alessandri) and Ecuador (Carlos Julio Arosemena) to make a joint “announcement forthwith that their Governments are prepared to sign a multilateral Latin American agreement whereby the countries would undertake not to manufacture, receive, store or test nuclear weapons or nuclear launching devices.” The Declaration aimed to inspire other Latin-American countries to eventually join and thus become part, for our people, of a liberating charter from all nuclear threat.

As soon as the President of Mexico had received the encouraging replies of the other four Latin American presidents, on 29 April 1963 in the capitals of the five countries was announced that by common agreement the declaration on the denuclearization of Latin America was from that moment solemnly adopted.

The President of Mexico addressed a message by radio and television to the Mexican people wanted to remove all possibility of a misinterpretation of the reasons which had led him to address, first of all, only four of the heads of state of Latin America. He stated:

“I now have only to explain to you why, although Mexico has always been known for its feelings of fraternal friendship and respect toward each and every one of the Latin American peoples, I decided, in this first phase of our enterprise, to address only the Heads of State that I have mentioned. The reason is simply that these four countries had the honour of co-sponsoring, at the last session of the General Assembly of the United Nations, a draft resolution which proposed the denuclearization of Latin America. At the request of the co-sponsors of the draft, discussion of this document was postponed. I therefore believed that I should suggest to these four States that it would be desirable to invite the other sister Republics to join us in our efforts to proscribe nuclear threats from Latin American lands. Furthermore, I am happy to announce that I shall lose no time in addressing fraternal messages to the Heads of State of the other Latin American countries, expressing the most fervent hope that we shall be able to count on their invaluable collaboration in this common enterprise.”

On that same date, the entire text of the Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of Latin America was published, which reads as follows:

“The Presidents of the Republics of Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador and Mexico,

Deeply concerned about the present turn of events in the international situation, which is conductive to the spread of nuclear weapons,

Considering that, in virtue of their unchanging peace-loving tradition, the Latin American States should unite their efforts in order to turn Latin America into a denuclearized zone, thus helping to reduce the dangers that threaten world peace,

Wishing to preserve their countries from the tragic consequences attendant upon a nuclear war, and

Spurred by the hope that the conclusion of a Latin American regional agreement will contribute to the adoption of a contractual instrument of world-wide application,

In the name of their peoples and Governments have agreed as follows:

-

To announce forthwith that their Governments are prepared to sign a multilateral Latin American agreement whereby their countries would undertake not to manufacture, receive, store or test nuclear weapons or nuclear launching devices;

-

To bring this Declaration to the attention of the Heads of State of the other Latin American Republics, expressing the hope that heir Governments will accede to it through such procedure as they consider appropriate;

-

To co-operate with one another and with such other Latin American Republic as accede to this Declaration, in order that Latin America may be recognized as a denuclearized zone as soon as possible.”

2.- Resolution 1911 (XVIII) of the UN General Assembly

Five days after the Joint Declaration of the five Latin American Presidents was made public, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, U Thant, held a press conference at the Palais de Nations in Geneva. Questioned by a newspaper correspondent on this Declaration, he replied:

“The mood of the United Nations General Assembly has always been in favour of the establishment of denuclearized zones in parts of the world. I think it was the feeling of most African nations last year and the year before that Africa should be made a denuclearized zone; and last week–actually a few days before I left New Nork–I received a communication from five Latin American Governments declaring their intention to make Latin America a denuclearized zone. My personal feeling is that that attitude on the part of a growing number of Member States of the United Nations should be welcomed, because I feel very strongly that any denuclearized area would represent some kind of territorial disarmament. I interpret this trend as some kind of territorial disarmament – a trend which should be welcomed.”

Three days later, on 6 May, the 128th meeting of the Eighteen-Nation Committee on Disarmament took place in Geneva. At this meeting, the representative of Brazil, Josué de Castro, and the representative of Mexico, Dr. Luis Padilla Nervo, officially presented to the Committee the Joint Declaration of the five presidents, giving a detailed exposition of its origin, objectives, and significance within the framework of disarmament.

Immediately after their intervention, almost all other members of the Committee expressed their opinion on the Declaration, either supporting the Latin American initiative or, at the very least, expressing that the declaration was received with interest.

The statements of the UN Secretary-General and the Members of the Committee on Disarmament–the body to which the General Assembly has entrusted the main responsibility for negotiations and therefore the one most qualified to deal with all matters connected with disarmament–strengthened the intention, that since the beginning was supported by the States who co-authored the Declaration, of having the full moral support of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) to the Latin American initiative. To that end, in a meeting that the representatives of the Declaration convened in in Mexico prior to the opening of the XVIII Session of the UNGA–which for the first time contained as a separate item in the agenda the matter of the denuclearization of Latin America, whence they agreed to push for the approval of a resolution in this regard.

As the Representative of Mexico in charge of this matter, I had the opportunity to prepare a preliminary draft resolution at the headquarters of the United Nations in October 1963 which after a few modifications made by, first, the other four States who co-authored the Declaration and later by the representatives of the Latin American Group, the preliminary draft resolution was submitted to the First Committee of the General Assembly with the co-sponsorship of the following eleven Latin American delegations: Bolivia, Brazil, Costa Rica, Chile, Ecuador, El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Panama, Uruguay and Mexico.

The preliminary draft was examined throughout the course of eight sessions at the UNGA First Committee between 11 and 19 November, and was finally adopted in the last session without any change. One week later, on 27 November, the plenary meeting of the UNGA approved the draft resolution and thus, it became resolution 1911 (XVIII). In its operative paragraphs, the General Assembly declared its support and encouraged the Latin American initiative, and requested the Secretary-General to provide the Latin American States with the technical support that may be required to achieve the purposes expressed in the resolution. The full text reads as follows:

“The General Assembly,

Bearing in mind the vital necessity of sparing present and future generations the scourge of a nuclear war,

Recalling its resolutions 1380 (XIV) of 20 November 1959, 1576 (XV) of 20 December 1960 and 1665 (XVI) of 4 December 1961, in which it recognized the danger that an increase in the number of States possessing nuclear weapons would involve, since such an increase would necessarily result in an intensification of the arms race and an aggravation of the difficulty of maintaining world peace, thus rendering more difficult the attainment of a general disarmament agreement,

Observing that in its resolution 1664 (XVI) of 4 December 1961 it stated explicitly that the countries not possessing nuclear weapons had a grave interest and an important part to fulfil in the preparation and implementation of the measures that could halt further nuclear weapon tests and prevent the further spread of nuclear weapons,

Considering that the recent conclusion of the Treaty banning nuclear weapon tests in the atmosphere, in outer space and under water, signed on 5 August 1963, has created a favourable atmosphere for parallel progress towards the prevention of the further spread of nuclear weapons, a problem which, as indicated in General Assembly resolutions 1649 (XVI) of 8 November 1961 and 1762 (XVII) of 6 November 1962, is closely connected with that of the banning of nuclear weapon tests,

Considering that the heads of State of five Latin American Republics issued, on 29 April 1963, a declaration on the denuclearization of Latin America in which, in the name of their peoples and Governments, they announced that they are prepared to sign a multilateral Latin American agreement whereby their countries would undertake not to manufacture, receive, store or test nuclear weapons or nuclear launching devices,

Recognising the need to preserve, in Latin America, conditions which will prevent the countries of the region from becoming involved in a dangerous and ruinous nuclear arms race,

- Notes with satisfaction the initiative for the denuclearization of Latin America taken in the joint declaration of 29 April 1963;

- Express the hope that the States of Latin America will initiate studies, as they deem appropriate, in the light of the principles of the Charter of the United Nations and of regional agreements and by the means and through the channels which they deem suitable, concerning the measures that should be agreed upon with a view to achieving the aims to the said declaration;

- Trusts that at the appropriate moment, after a satisfactory agreement has been reached, all States particularly the nuclear Powers, will lend their full co-operation for the effective realization of the peaceful aims inspiring the present resolution;

- Requests the Secretary-General to extend to the States of Latin America, at their request, such technical facilities as they may require in order to achieve the aims set forth in the present resolution.”

1265th plenary meeting,

27 November 1963

After resolution 1911 (XVIII) was definitively adopted at the plenary meeting of 27 November 1963, I had the opportunity to deliver a short speech as the spokesperson of the Mexican Delegation. In it I emphasized the fact that the resolution represented at the same time a challenge and a testimony. It was a testimony that Latin America had come of age and is able to assess correctly the real aspirations of its people. It was a challenge to the ability of Latin American States to work together and achieve unanimous results reflecting the intense desire for peace that is certainly felt by all its people.

After presenting the main purposes of the prohibition of nuclear weapons enterprise in Latin America, I concluded by asserting:

“We do not intend to act rashly or hastily. We shall make haste slowly, as advised by the old Latin proverb, but we shall make haste.

Today, with the historic resolution adopted by this Assembly, Latin America starts along the road to denuclearization. And we are convinced that sooner or later we shall attain that goal, because we can count on the unqualified and enthusiastic support of all our peoples.”

Those words clearly foreshadowed a behavioural pattern that would soon be proven in facts.

3.-The creation of COPREDAL

Following the conclusion of the XVIII period of sessions of the UNGA, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico began active consultations with the other Republics in Latin America on the procedures that might be most efficient for carrying out the goals considered in resolution 1911 (XVIII).

The outcome of those consultations was the Preliminary Meeting on the Denuclearization of Latin America (REUPRAL, for the Spanish acronym) which was held from 23 to 27 November 1964. Almost all Republics of Latin America, except for Guatemala, participated and voted in favour of the resolution. The meetings of the Preliminary Meeting were held in one of the buildings of the Mexican Institute of Social Security known as “Unidad Independencia”, located in San Jerónimo Lídice, Federal District (now Mexico City.)

The adopted agenda in the opening meeting depicted the serious concern of the participating States of following the responsibilities set out in UNGA Resolution 1911. It was understood that although the States did not want to hasten discussions, they did not intend to waste time on fruitless topics either. The two items included in the agenda clearly proved this fact, which are as follows:

-

“Measures that should be agreed upon with a view to achieving the purposes of the denuclearization of Latin America, as set forth in the Declaration of 29 Abril 1963 and reiterated in resolution 1911 (XVIII) of the United Nations General Assembly.

-

Preliminary examination of the principal considerations involved in the conclusion of a contractual instrument on the denuclearization of Latin America.”

At the same opening session, the Meeting proceeded to elect the Members of its General Board. I had the honour of being appointed as Chairman, as it is customary to designate this position to the representative of the host country. The representatives of Brazil and El Salvador, Ambassador José Sette Cámara and Ambassador Rafael Eguizábal Tobías respectively, were appointed also by acclamation for the two Vice-chairmen seats. Mexican Ambassador Carlos Peón del Valle served as General Secretary of the Meeting. The configuration of these seats would remain for the two-year operation of the Preliminary Commission for the Denuclearization of Latin America (COPREDAL, for the Spanish acronym), held from March 1965 to February 1967. During the second part of the fourth and final session of the Preparatory Commission, Ambassador Sergio Correa da Costa replaced Ambassador Sette Cámara, who was unable to attend the Meeting.

During its brief period of sessions, REUPRAL adopted two significant resolutions. The first one reaffirmed the purposes of the denuclearization in Latin America previously stated in the Declaration of the five Presidents and later ratified in Resolution 1911 (XVIII), where the term “denuclearization shall mean the absence of nuclear weapons.” The second resolution, whose importance is difficult to exaggerate, REUPRAL, acting as constitutional Assembly, created the Preliminary Commission for the Denuclearization of Latin America (COPREDAL), which was given the specific task of preparing “a preliminary draft of a multilateral treaty for the denuclearization of Latin America and to undertake the preparatory studies and measures which it considers appropriate.”

The resolution included, among others, the following paragraph which mandated the Preliminary Commission to establish certain subsidiary bodies:

“The Commission shall constitute from its membership the working groups which it deems necessary and which shall perform their functions either at the headquarters of the Commission or elsewhere, as appropriate, and a committee to co-ordinate their work, to be called the ‘Co-ordinating Committee.’”

The Commission was recommended to give priority in its work to the following matters:

- The definition of the geographical boundaries of the area to which the treaty should apply;

- The methods of verification, inspection and control that should be adopted to ensure the faithful fulfilment of the obligations contracted under the treaty;

- Actions designed to secure the collaboration in the Commission’s work of the Latin American Republics that were not represented at the Preliminary Meeting;

- Action designed to ensure that the extra-continental or continental States which, de jure or de facto international responsibility for territories situated within the boundaries of the geographical area to which the treaty applies, agree to contract the same obligations with regard to those territories as the abovementioned Republics contract with regard to their own;

- Action designed to obtain from the nuclear Powers a commitment to the effect that they will strictly respect the legal instrument on the denuclearization of Latin America as regards all its aspects and consequences.

In the same resolution, REUPRAL also agreed on the headquarters of COPREDAL, which would be located in Mexico and be composed of the seventeen Latin American Republics which have participated in the Preliminary Meeting along with those which subsequently adopt the foregoing resolution; that the Commission should adopt its own Rules of Procedure, and that the first meeting of the Preparatory Commission be fixed to 15 March 1965. Finally, REUPRAL requested to the Government of Mexico to appoint the General Secretary of the Preparatory Commission and the necessary staff for the secretariat of the Commission.

The closing meeting of REUPRAL took place on 27 November 1964, which happily coincided with the very date on which, a year ago, the UNGA adopted Resolution 1911 (XVIII). In accordance with resolution II of REUPRAL–less than four months after the closing meeting of REUPRAL–the Preparatory Commission was celebrating its first period of sessions on 15 March 1965 at the same building in San Jerónimo Lídice. The first period of sessions would finish on 22 March, one week later.

The adopted agenda for the period of sessions was even more decisive than the one from REUPRAL:

“Preparation of the preliminary draft of a multilateral treaty for the denuclearization of Latin America and, to that end, execution of the preparatory measures and studies referred to in resolution II of the Preliminary Meeting on the Denuclearization of Latin America.”

The Commission adopted its Rules of Procedure that, without going into much detail, included all the necessary provisions to facilitate the correct functioning of the Commission. The most important articles of the Rules of Procedure were undoubtedly those referring to the establishment of the working groups and some fundamental aspects of the Co-ordinating Committee. All decisions approved by the Commission in its first period of sessions regarding the organization, powers and functioning of the Co-ordinating Committee and the three working groups were included in Resolution No. 1 (I) entitled “Organization of the work of the Preliminary Commission for the Denuclearization of Latin America” as it is recorded in the last version of the respective Final Act.

The same resolution established that the Co-ordinating Committee could request to the Secretary-General of the United Nations “such technical facilities as they may require in order to achieve the aims set forth in the resolution” and, in resolution No. 4 (I) COPREDAL asked the Chairman of the Commission to transmit to the Secretary-General of the United Nations the text of the Final Act of its first period of sessions, with the request that he should have it distributed as a General Assembly document for the information of Members of the United Nations in connexion with resolution 1911 (XVIII), paragraph 2.

COPREDAL interpreted the resolution to be permanently valid and, consequently, the Chair transmitted the Commission’s subsequent period of sessions’ Final Act to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, requesting the same abovementioned. As a result, all final documents were reproduced, translated to the official languages of the United Nations, and distributed to all Members as official documents of the General Assembly, which greatly facilitated its consultation at international forums.

4.- Preparation of the preliminary draft articles for the Treaty on the denuclearization of Latin America and a Declaration of the Principles.

While prominent decisions of the first period of sessions were those related to the organization of the work of COPREDAL and the adoption of its Rules of Procedure, at the second period of sessions the decisions were focused on the establishment of a verification, inspection and control system; the approval of a declaration of the principles that, according to the resolution, should “serve as a basis” for the Preamble of the preliminary draft of the Treaty for the military Denuclearization of Latin America, and the constitution of a Negotiating Committee as well.

The main aspects of these three matters were as follows.

As it was previously mentioned, immediately after being established, COPREDAL created three working groups with the task of transmitting by 1 August 1965 the reports that would be submitted by the Co-ordinating Committee to the Preparatory Commission in order to be considered by the latter at its second period of sessions. In accordance with the foregoing, the three groups presented substantial reports on the work that they managed to accomplish in their five months of work.

Working group A was in charge of presenting proposals for the definition of the geographic boundaries of the area to which the multilateral treaty for the denuclearization of Latin America should apply, and to take actions in order to secure the collaboration in the Commission’s work of any Latin American Republic which is not yet a member of the Commission and of all other sovereign States, present or future, situated within the prospective boundaries of the area.

Working Group C was responsible for action designed to obtain from the nuclear Powers a commitment to the effect that they will strictly respect the legal instrument on the denuclearization of Latin America as regards all its aspects and consequences. Its reports, as it was indicated in the same, had a preliminary character.

Regarding Working Group B, whose mandate consisted in conducting a study on the methods of verification, inspection and control which should be adopted to ensure the faithful fulfilment of the obligations contracted under the treaty. Its report included preliminary draft articles on the matter that allowed afterwards to be regarded as, unlike most multilateral instruments on disarmament, the provisions for disarmament control which should be adopted as soon as possible.

Working Group B began its work on 14 May 1965 and, on that same day, agreed to request the Chair of COPREDAL to transmit to the Secretary-General of the United Nations–highlighting the UN Secretariat’s as “the most important repository of knowledge and experience on the matter” that the Group would take charge in–based in the provisions set forth in paragraph 4 of Resolution 1911 (XVIII), a petition asking the cooperation of the Secretary-General in order to provide them the technical facilities indicated below:

“A. The urgent preparation of the following working documents:

- A selected compilation of the most significant proposals presented by States, specialized institutions or experts, to guarantee the verification and control of nuclear disarmament, and

- A classification, arranged by specific topics, of the contents proposed and other material included in the previous working document.

B. The registration of Working Group B as a Technical Consultant, for a one-month period, and if possible, the appointment of an officer of the United Nations Secretariat, expert on the matter assigned to the Group, as of 15 June 1965.”

Regarding the request, the United Nations Secretary-General facilitated Group B the services of Mr. William Epstein, Chief of Disarmament Affairs Group of the United Nations Secretariat, and transmitted them three documents which contained a significant compilation of background information regarding control in disarmament, particularly nuclear disarmament.

After celebrating five sessions in which the working documents prepared by the UN Secretariat were analysed and the Technical Consultant of the UN was heard, the Group agreed, alongside the Secretariat of COPREDAL, to prepare the preliminary draft articles for the Treaty. Once the preliminary draft was ready, the group deliberated the foregoing in various sessions and, after a few modifications, it was adopted and forwarded to the Co-ordinating Committee in order to be submitted to the Preparatory Commission as an annex to its report entitled, “Preliminary draft articles for the Treaty for the Denuclearization of Latin America relating to verification, inspection and control.”

The Preliminary Commission adopted resolution 9 (II) after receiving the verdict of a sub-commission, which, among other things, was in charge of examining the preliminary draft articles. Through resolution 9 (II), the Preliminary Commission–after having considered with especial appreciation the preliminary draft– took into account the fact that the highly technical nature of some of the provisions of the foregoing makes it necessary for the them to be studied by the Member States.

In light of the abovementioned, the Commission resolved to transmit the preliminary draft to the governments of the Member States and requested them to transmit their observations on the foregoing to the General Secretary of the Commission “no later than 15 January 1966; requesting them to arrange, so far as possible, said observations to be presented in a suitable form for direct use in the preparation of the articles of the Treaty.”

The Commission also agreed to request the Co-ordinating Committee to prepare, on the basis of the preliminary draft articles annexed to the resolution and of such observations as the Governments may make, a working paper for use in drafting a new version of the preliminary draft, and to transmit to the Governments, by 28 February 1966 at the latest, the working paper abovementioned.

Finally, COPREDAL expressed through its gratitude to the UN Secretary-General and to the Technical Adviser for their contribution to the Commission’s work.

Even though the preliminary draft articles, as the title suggests, were prepared to serve as a basis for the study of the Treaty’s articles despite being subject to various additions and modifications of secondary nature, its quality should allow its essential provisions to be incorporated into the future treaty.

The origin of the second matter–the elaboration of a declaration of the principles that would serve as the preamble for the instrument in preparation–was basically the following:

The Co-ordinating Committee, in its third session held on 9 August 1965, decided to entrust the Secretariat of COPREDAL with the preparation of a working document that contained “helpful elements for the drafting of the preamble of the preliminary draft of the multilateral Treaty for the denuclearization of Latin America.”

The Preparatory Commission, in its fourteenth session convened on 27 August of 1965, established a sub-commission to which it transferred the task of studying various documents, among others, the working document prepared by the Secretariat as requested by the Co-ordinating Committee. The foregoing was reproduced with the classification COPREDAL/S/DT/1.

In its sixteenth session held on 31 August, the Commission considered the draft resolution COPREDAL/L/8 that was submitted by the sub-commission and the which incorporated the text prepared by the Secretariat with minor modifications; the main modification consisted in adding, as final consideration, an explicit reference to UNGA Resolution 1911 (XVIII).

In the same session, the Commission, addressing the observations delivered by some representatives, agreed that the draft resolution be modified to “Decides, to approve as a declaration of the principles which shall serve as a basis for the Preamble of the preliminary draft of a Multilateral Treaty […]” instead of “Decides, to approve as a Preamble of the preliminary draft of the Multilateral Treaty […]” which was adopted by unanimous approval.

In the following two periods of sessions, the aforesaid declaration of principles would be subject to slight amendments which consisted in adding the fourth, sixth and seventh provisions of what would be the Treaty’s Preamble; in the section of the Preamble starting with “Convinced that”, the addition of the paragraph referring to the fact that “the establishment of militarily denuclearized zones is closely related to the maintenance of peace and security in their respective regions” and two clauses, one indicating and another one broadening the meaning of other paragraphs. Besides those additions, the reference to nuclear weapons launching devices stated in paragraphs ninth and thirteenth of the Declaration of Principles was omitted.

Therefore, it can be certainly said that the Preamble of the future Treaty was practically adopted, after the Preparatory Commission adopted the Declaration of the Principles on 31 August 1965, which I have been referring to and which I include herewith:

“In the name of their peoples and faithfully interpreting their desires and aspirations, the Governments represented at the Conference of Plenipotentiaries for the Denuclearization of Latin America,

Desiring to contribute, so far as lies in their powers, toward the armaments race, especially in nuclear weapons, and towards strengthening a world at peace, based on the sovereign equality of States, mutual respect and good neighbourliness;

Recalling that the United Nations General Assembly, in its resolution 808 (IX), adopted unanimously as one of three points of a co-ordinated program of disarmament “the total prohibition of the use and manufacture of nuclear weapons and weapons of mass destruction of every type, together with the conversion of exiting stocks of nuclear weapons for peaceful purposes” and,

Recalling also United Nations General Assembly resolution 1911 (XVIII), which established that the measures that should be agreed upon for the denuclearization of Latin America should be taken “in the light of the principles of the Charter of the United Nations and of regional agreements”,

Convinced:

That the incalculable destructive power of nuclear weapons has made it imperative that the legal prohibition of war should be strictly observed in practice if the survival of civilization and of mankind itself is to be assured,

That nuclear weapons, whose terrible effects are suffered, without distinction and without scape, by the armies and by civilian population alike, constitute, through the persistence of the radioactivity they release, an attack to the integrity of the human species and ultimately may even render the whole Earth uninhabitable,

That general and complete disarmament under effective international control is a vital matter which all the peoples of the world equally demand,

That the proliferation of nuclear weapons, which seems inevitable unless States, in the exercise of their sovereign rights, use self-restraint in order to prevent it, would make any agreement on disarmament enormously more difficult and would increase the danger of the outbreak of a nuclear conflagration;

That the privileged situation of the States represented at the Conference, whose territories are wholly free from nuclear weapons and their launching devices, imposes upon them the inescapable duty, of preserving that situation both in their own interests and for the good of mankind;

That the existence of nuclear weapons in any country of Latin America would make it a target for possible nuclear attacks and would inevitably set off, throughout the region, a ruinous race in nuclear weapons which would involve the unjustifiable diversion, for warlike purposes, of the limited available resources required for economic and social development;

That the foregoing factors, coupled with the traditional peace-loving outlook of their peoples, makes it essential that nuclear energy should be used in Latin America exclusively for peaceful purposes,

That the denuclearization of vast geographical areas, adopted by the sovereign decision of the States comprised therein, will exercise a beneficial influence on other regions;

Convinced, finally:

That the denuclearization of the States represented at the Conference–being understood to mean the undertaking entered into internationally in this Treaty to keep their territories free for ever, as they have been hitherto, from nuclear weapons and their launching devices–will constitute a measure of protection for their peoples against the squandering of their limited resources on nuclear armaments and against possible nuclear attacks upon their territories; a significant contribution towards preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons; and a powerful factor for general and complete disarmament, and

That Latin America, faithful to its deep-seated tradition of universality of outlook, must endeavour not only to banish from its homelands the scourge of nuclear war and to strive for the well-being and advancement of its peoples, but also, at the same time, to co-operate in the fulfilment of the ideals of mankind, that is to say in the consolidation of a lasting peace based on equal rights, economic fairness and social justice for all, in accordance with the principles and purposes of the Charter of the United Nations,

Have agreed as follows: […]”

It is worth mentioning that the third resolution, among those approved in the second period of sessions, which in the Final Act of that session has the classification 7 (II) by the which, as I previously mentioned, established the Negotiating Committee that, in practice, replaced Working Group A and C, and together with the Co-ordinating Committee became one of two principal subsidiary bodies of COPREDAL.

5.-The contribution of the Co-ordinating Committee

The Co-ordinating Committee was planned by the Preliminary Meeting and established by COPREDAL in its first period of sessions. In accordance with Article 14 of its Rules of Procedure, the Co-ordinating Committee was integrated by the Chairman and the two Vice-chairmen of the Preparatory Commission, who were the Representatives of Mexico, Brazil and El Salvador respectively, and the Representatives of Ecuador and Haiti, Ambassador Leopoldo Benites Vinueza and Ambassador Julio Jean Pierre-Audain, who were also the Chairman and Vice-chairman of Working Group A and B respectively. There was no need for an additional member of Working Group C since the representative of Brazil, Ambassador José Sette Cámara, was one of the two Vice-chairmen of the Preparatory Commission.

The constructive influence of the Co-ordinating Committee and the results of its productive work was evident in numerous occasions throughout the work of the Preliminary Commission. One of the most salient examples of its work was the elaboration of a working document already drafted in the form of a preliminary draft of the Treaty, that was submitted in the third period of sessions of COPREDAL.

The Co-ordinating Committee was able to complete this task thanks to the provisions of the Treaty’s preamble and control system that were already approved in the second period of sessions of COPREDAL, and with the submission by the Mexican Delegation of the observations that the Preparatory Commission made to the working document requested in its Resolution 9 (II), which was drafted in the form of a preliminary draft of the Treaty.

Based on those three documents and considering some general preliminary observations submitted by Chile, as well as a draft resolution submitted by Argentina for the establishment of a “permanent Latin American denuclearization Committee” in the first period of sessions of COPREDAL, the Co-ordinating Committee prepared the foregoing working document in the course of nine sessions held between 8 and 14 March 1966, which was entitled “Preliminary Draft of the Treaty for the Denuclearization of Latin America.”

In the Preliminary Draft, which contained a preamble and twenty-five articles, the declaration of principles was retaken with the elimination of the phrase “and launching devices” in paragraphs ninth and thirteenth since a distinction should be drawn between instruments for the transport or propulsion of nuclear weapons– which were separable from the device and those which were an indivisible part thereof–or otherwise the absurd situation would arise where most commercial aircraft would be prohibited, since they are capable of being used as vehicles for the launching of certain nuclear weapons.

If the preparation of the Preliminary Draft of the Treaty gave extraordinary momentum to the efforts of COPREDAL, the contribution of the Committee in its last report, dated 28 December 1966, constituted undoubtedly an element to COPREDAL that allowed it to complete the much requested task of the Treaty of Tlatelolco, which was unanimously approved in its fourth period of sessions.

Indeed, there was a compromise stated in the abovementioned report that the Committee was able to reach as a result of two meetings held at the headquarters of the Permanent Mission of Mexico to the United Nations on 27 and 28 December 1966. In order to assess the value of its results, it is convenient to briefly summarize some of its most exemplary precedents.

The entry into force of the Treaty was probably the question that provoked the most prolonged discussions in the Preparatory Commission, and its solution involved overcoming major obstacles. When it was first taken up on the Commission in April 1966, two distinct schools of thought emerged.

According to the first– and its sponsors included Mexico from the very outset–the Treaty would enter into force, in accordance with the rule generally applicable in such cases, in respect of those States which had ratified it, on the date on which their instruments of ratification were deposited. With regard to the Latin American Agency set up under the Treaty, its entry into operation would come about as soon as eleven instruments of ratification had been deposited, that number being a majority of the twenty-one members of the Preparatory Commission.

The States belonging to the second school of thought, on the other hand, held that even when the Treaty had been signed and ratified by all the States members of the Preparatory Commission, it would only enter into force when four conditions had been fulfilled-essentially those which appear in article 28, paragraph 1, of the Treaty of Tlatelolco. These may be summarized as follows: signature and ratification of the Treaty and of Additional Protocols I and II by all the States to which the three instruments in question were open for signature, and the conclusion of agreements with the International Atomic Energy Agency on the application of its Safeguards System by all the States signatories of the Treaty and Additional Protocol I.

Since it proved impossible to find a solution to the problem raised by these two schools of thought at the third session, the Preparatory Commission incorporated into the Proposals approved by it on 3 May 1966 two parallel texts setting forth the provisions that would appear in the Treaty if the first alternative were accepted and those that would appear if the second were preferred.

To resolve the problem, the Co-ordinating Committee suggested in its report of 28 December 1966 that a conciliatory formula be adopted that might receive the support of all States member of the Commission without detracting in any way from the different positions on the substance of the question as crystallized in the two alternative texts included in the proposal.

It was this formula that with certain modifications was finally adopted and incorporated in article 28 of the Treaty. It provided that the Treaty would enter unto force for all signatory States only when the four requirements set forth in paragraph 1 of article 28 had been complied with. Nevertheless, as it is stated in paragraph 2 of the article, “All signatory States shall have the imprescriptible right to waive, wholly or in part, the requirements laid down in the preceding paragraph. They may do so by means of a declaration which shall be annexed to their respective instrument of ratification and which may be formulated at the time of deposit of the instrument or subsequently. For those States which exercise this right, this Treaty shall enter into force upon deposit of the declaration, or as soon as those requirements have been met which have not been expressly waived.”

As it can be seen, an eclectic system has been adopted which, while respecting the views of all signatory States, makes it impossible for any one of them to attempt to veto the entry into force of the Treaty for those States which wish to submit voluntarily to the status of denuclearization as defined and set forth in the Treaty.

6.- Approval and opening for signature of the Treaty of Tlatelolco

On 12 February 1967, COPREDAL unanimously approved the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America. Two days later, the Treaty was opened for signature at the headquarters of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Mexico located in the Aztec-named neighbourhood Tlatelolco, in the capital of Mexico.

I cannot find anything better to reflect the predominant sentiments in both occasions than to repeat herewith some paragraphs from the interventions that I had the privilege of deliver.

In the first occasion, I began by underlining the fact that we had just “approved the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America, through whereby we hope to forever banish from our homelands this horrible threat posed by those instruments of mass destruction, whose reach is not only unmeasurable but its effects are proven to be truly terrifying.” I finished by addressing the Representatives of the Member States as follows:

“Ladies and gentlemen:

Throughout my career as an internationalist and a diplomat I had the opportunity to attend to fifty international conferences, some of which I chaired. However, I can assure you that, for me, the most important one among all of those was the Preliminary Commission for the Denuclearization of Latin America, for which two years ago I was honoured of being appointed as Chairman. I am convinced, indeed, that I am not going to be given again the opportunity of contributing, at least not to the same level that your generous co-operation made it possible in this case, to an enterprise with such noble and ambitious purpose like the one we have happily achieved: to lay the foundations to ensure in Latin America, through a multilateral Treaty sovereignly concerted, and which we hope will receive universal observance, the complete and permanent absence of those horrific instruments of mass destruction that are nuclear weapons, thus solemnly prohibit, for ever, nuclear weapons in Latin America.”

Regarding the closing session of COPREDAL, the following words that I would like to recall are taken from the speech I delivered on 14 February 1967:

“It is a privilege for Mexico of having been able to contribute to the elaboration of this task that the Governments and peoples of our America entrusted to the Preliminary Commission. The signature of the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America stands not only as a landmark but also goes beyond that of the field of nuclear disarmament; it contributes in a concrete way to the promotion of international peace and security, With the conclusion of its work, the Preparatory Commission offers to the world an inspirational example of the first Treaty ever concluded which will guarantee the complete absence of nuclear weapons in a region inhabited by man.

The Representatives who are gathered here can, with ample justification, take pride in what they have wrought by their own initiative and through their own efforts. But even more than you, we shall congratulate the peoples of Latin America. The entry into force of the Treaty would mean that we prevented, before it started, the dissemination of nuclear weapons in any form whatsoever. Latin America will not have to endure ever the intolerable burden that those weapons entail. And its territories untainted by atomic sites that threaten other countries, will not attract nuclear attacks from possible opposing powers.

There will certainly not be wanting persons who will say, and of course quite rightly, that this is not a perfect treaty, that is suffers from defects and could be better. Still, I do not think that need to worry us, because it applies to all products of human efforts, which are essentially open to improvement. My own conviction is that the Treaty, despite its limitations, is destined to exercise a moral influence of incalculable value […]

Of course, military denuclearized zones do not constitute an end to itself but rather a means for achieving, at a later stage, general and complete disarmament that, as the United Nations General Assembly has adopted more than a decade ago, one of its main objectives is the total prohibition of the use and manufacture of nuclear weapons and weapons of mass destruction of every type. It is evident, however, that given the current international context of a world that finds itself divided, it would be naive to think that such an ambitious goal can be achieved in the short term. For some time now, Mexico has supported a procedure that, without losing focus on the ultimate goal, allowed effective progress in different phases. To that end, we share wholeheartedly with what is declared in the Preamble of the Treaty where it emphasizes that military denuclearization of Latin America will not only spare their peoples from the squandering of their limited resources on nuclear armaments and will protect them against possible nuclear attacks, but will also constitute a significant contribution towards preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapons and a powerful factor for general and complete disarmament. We are confident that that it will exercise a favourable influence in the negotiations that will resume in Geneva the following week for the conclusion of a nuclear non-proliferation treaty. We also hope that it can help other regions, that have similar conditions as Latin America, to be as fortunate as us in their efforts towards military denuclearization.

On the other hand, the agreement reached on a difficult and complicated matter like the one discussed in this hall, demonstrates the capacity of the Latin American countries to engage in common enterprises of great ambition and particular significance. The fruitful solidarity that this Treaty created should now be used for other tasks of the same urgency for our countries, among which I would like to highlight expansion and acceleration of the economic integration, and tightening and strengthening its coordinated action in all levels for the greatness of its peoples. If we persevere with the same fervour in these endeavours, the realm of peace that we have forged will too one day become a realm of prosperity and wellbeing.

Ladies and gentlemen:

After the long road traversed since the Preliminary Commission for the Denuclearization of Latin America’s first period of sessions almost two years ago, today we have arrived victorious to the goal set out by the same Commission.

I consider that we can feel fully satisfied with the results. The Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America, with which we have put an end to our deliberations in this corner of Tlatelolco, constitutes an instrument of peace and mutual understanding and whose future implications will be more evident over time, which from now on I believe it can be firmly expressed that all you deserve the gratitude of posterity.”

7.- The inauguration of the General Conference of OPANAL

From 24 to 28 June 1969, the Preliminary Meeting for the constitution of the Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America was held in Mexico City. There were eight draft resolutions approved at that meeting that covered the following topics: the Rules of Procedure of the General Conference, the Agreement between OPANAL and the Government of the Host State, the Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of OPANAL; the Staff Regulations of the Agency’s Secretariat, the Financial Regulations of OPANAL; the Budget of the Agency for fiscal year 1969-1970; the Scale of Assessed Contributions prorated for the expenses of the Agency, and the establishment of a Working Capital Fund for the Agency.

The General Conference of the Agency dedicated the first period of sessions of its “supreme organ” (the General Conference) almost entirely to the examination and approval of the abovementioned drafts, having also adopted important decisions like the appointment of Ambassador Carlos Peón del Valle, who served as the Secretary General of COPREDAL throughout its four periods of sessions, as Acting Secretary-General of the General Conference. The interim period ended in the second half of the first period of sessions of the General Conference, when through resolution 30 (1), Ambassador Leopoldo Benites Vinueza was appointed the Secretary-General of OPANAL for a four-year period starting on 1 January 1971.

At the beginning of the debate of the General Conference, the United Nations Secretary-General, U Thant, delivered a statement, which amongst other things, he said:

“It is a great pleasure and indeed an honour for me to be in Mexico City at the inauguration of the General Conference of the Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America, which is known by its Spanish acronym, OPANAL. The Agency is in a sense an offspring of the United Nations. In November 1963, by resolution 1911 (XVIII), the General Assembly first gave its blessing and encouragement to the idea of creating a nuclear-free zone in Latin America. The establishment of such a zone, it was felt, would not only be of great benefit to the people of Latin America by assuring their security and permitting them to concentrate their energies and resources on peaceful economic and social pursuits, but it would also be of benefit to the people of the world as a whole by eliminating the threat of a nuclear arms race and of nuclear war from an important area of the world, and thus help to promote the cause of disarmament and of international peace and security[…]

It is no secret that, as is the case with any great endeavour or pioneering project, there were some who had serious doubts as to whether the States of Latin America could succeed in their work or achieve any concrete results. Nevertheless, they persisted in their efforts and made steady progress year by year towards the attainment of their objective. Today we see the culmination and the fruition of five years of difficult and painstaking work. I would like to extend my sincere congratulations to all the Governments and statemen who have laboured so long and so well to arrive at the goal you have reached today, and in particular to the Government of Mexico, which has been host to all your meetings […]

It is a matter of profound regret to me that successes in the field of disarmament have been few and far between. It is, of course, easy to appreciate the great obstacles that make progress in the field of disarmament and arms control so slow, so complicated and so frustrating. But these very difficulties make your achievement all more remarkable and significant. In a world that all too often seems dark and foreboding, the Treaty of Tlatelolco will shine as a beacon light. It is a practical demonstration to all mankind of what can be achieved if sufficient dedication and the requisite political will exist.

The Treaty of Tlatelolco is unique in several respects. It is true that the Antarctic Treaty and the Outer Space Treaty have prevented an arms race from taking place in those regions, and that concerted international efforts are now being undertaken to keep the arms race from spreading to the sea-bed and the ocean floor. All these regions have an element in common in that they are not inhabited. The Treaty of Tlatelolco is unique in that it applies to an important inhabited area of the earth. It is also unique in that the Agency which is being established at this session will have the advantage of a permanent and effective system of control with a number of novel features. In addition to applying the safeguards of the International Atomic Energy Agency, the regime under the Treaty also makes provision for special reports and enquiries and, in cases of suspicion, for special inspections. There is embodied in your Treaty a number of aspects if the system known as “verification-by-challenge”, which is one of the more hopeful new concepts introduced into the complicated question of verification and control.”

In my capacity as Chairman of the foregoing period of sessions of the General Conference, I had the opportunity to close the interventions of the opening meeting. The following paragraphs are part of my intervention:

“Tuesday, 2 September 1969, will be a date never forgotten, not only on the annals of Latin America, but also in the history of humanity’s efforts to eliminate nuclear weapons and contribute to the strengthening of peace.

To realize that there is no exaggeration in the preceding statement, it is sufficient to reflect for a moment that the nuclear-weapon-free zone which is the objective of the Treaty of Tlatelolco will one day cover the whole area of the Latin American subcontinent, and that it already contains more than 5.5 million square kilometres, consisting not of expanses of eternal snows or of uninhabited celestial bodies, but of fertile lands inhabited by approximately 100 million human beings.

It should not be forgotten that the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America is the only international instrument now in force designed to ensure through an effective international control system under its own permanent supervisory body, the total absence of nuclear weapons in a densely populated region of the earth. I take the world “absence” from the definition which, in November 1964, was incorporated in the first resolution adopted by the Preliminary meeting on the Denuclearization of Latin America. “Absence” is a conception of pellucid clarity, which does not lend itself to false or subtle interpretations, and can mean nothing else than the non-existence in perpetuity of nuclear weapons in the territories of the Contracting Parties, whatever State may have such weapons under its dominion or control.

It can therefore be asserted with every justification that the establishment of a nuclear-weapon-free zones constitutes an effective method of nuclear disarmament, and that if it should prove feasible to bring into force a universal treaty on the lines of the Treaty of Tlatelolco, the problem of nuclear disarmament will have been automatically solved, since that would entail the abolition of the vast nuclear arsenals which at present exist in the world.

For the States of Latin America which are already Parties to the Treaty, as for those which will accede to it in the future, the regime of total military denuclearization established under the Treaty entails a two-fold benefit: that of removing from their territories the danger of being converted into a possible target for nuclear attack, and that of avoiding the wastage of their resources, indispensable for the economic and social development of their peoples, on the production of nuclear weapons. […]

The Agency for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America, which is known by the initials OPANAL and whose principal and fully representative organ, the General Conference, is today beginning its work, represents the culmination of almost five years of joint and persevering effort by the Latin American States since the Preliminary Meeting of November 1964. The Agency’s goal will be to ensure the practical implementation of the provisions of the Treaty and the attainment of its two fundamental aims, to which I referred earlier: to guarantee the total absence of nuclear weapons and, in an equitable manner, to promote the use of the atom for peaceful purposes. […]

In concluding my speech, I think I can usefully revert to the point which I raised at the beginning.

I am convinced that all the Member States participating in this first session of the General Conference will unreservedly share the wish expressed by the President of Mexico in the message he has just addressed to the Conference, that OPANAL should very soon embrace all the countries in our region.

When this happens, and when, in addition, the Treaty of Tlatelolco extends to all the other territories forming part of this region, a statute enforcing absolute prohibition of nuclear weapons will apply throughout an area of more than 20 million square kilometers with a population, and the present density level, of some 260 million human beings.

This is the ideal we must pursue, and its attainment must be one of OPANAL’s chief tasks.”

(*) This text was published in the commemorative book of "The Twentieth Anniversary of the Treaty of Tlatelolco (1967-1987)" Page 11-35, OPANAL.